SRA response

Ministry of Justice consultation on Preserving and Enhancing the Quality of Criminal Advocacy

Published on 02 December 2015

Download consultation paper: Preserving and Enhancing the Quality of Criminal Advocacy (PDF 34 pages, 256K)

Introduction

The Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) is the independent regulator of solicitors and law firms in England and Wales. We regulate individual solicitors, certain other lawyers and non lawyers with whom they practise, solicitors' firms and their staff.

We are writing in response to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) consultation on Preserving and Enhancing the Quality of Criminal Advocacy.

The criminal advocacy market is experiencing change: the volume and complexity of cases reaching the Crown Court is reducing; solicitor advocates in their own right (and acting as the instructing solicitor) are undertaking the majority of criminal advocacy in the magistrates courts and are undertaking an increasing proportion of Crown Court advocacy; and the CPS has moved to a mixed model of in-house and external advocates. These changes in delivery, although specific to this market, are consistent with wider changes in the legal services market as a whole. These changes began with the beginning of market liberalisation in the 1980s but have accelerated following the Legal Services Act 2007: government legislation designed specifically to enable such changes through liberalisation and the removal of anti-competitive regulatory restrictions. Current government policy is to support and accelerate these changes for the benefit of the consumers of legal services and to support economic growth.

Attached as an annex to this response is an analysis of a number of these market changes, including changes in the level of demand for these services.

In this response we draw on the submission of the Legal Services Board (LSB) to the Jeffrey review. As oversight regulator, the LSB is well placed to provide an independent and objective assessment of the issues. Following a thorough review of the available evidence, the LSB reached the following conclusions:

- The criminal advocacy market is changing. Facilitated by liberalising changes by regulators, the provider base as a whole is adjusting to service the changing market.

- The evidence does not suggest that there are too few advocates to meet consumer need at any tier of court. Although data is very limited, it is also too early to conclude that there are risks of under supply in the medium-term. Quality issues are being addressed by the regulators through the Quality Assurance Scheme for Advocates (QASA).

- Increasing financial pressure, legal aid contracting incentives, stakeholder quality expectations, and pressure to reduce court time and increase efficiency all point to a greater proportion of the available work being delivered through larger, more varied and mixed skill providers. Neither regulation nor broader public policy should seek to obstruct this development to protect historical business models. There should be no unnecessary obstructions to the kinds of structures that can emerge and who can own them.

We support these conclusions. In reaching our view, we are not representing solicitors but trying to deliver a competitive legal market that works for consumers of criminal advocacy services. Consumers' needs are best met by a functioning, competitive market supported by rigorous competency based assessment to assure professional standards. The solution to any shortcomings in standards of criminal advocacy is to introduce a proper quality assurance system for identifying, reporting and addressing poor standards as we are doing through both QASA and our Training for Tomorrow programme, rather than protecting old patterns of practice or prescribing additional input requirements such as specified training.

Q1: Do you agree that the government should develop a Panel scheme for criminal defence advocates, based loosely on the CPS model already in operation? Are there particular features of the CPS scheme which you think should or should not be mirrored in a defence panel scheme?

We do not have a view on this and believe that it is for the government in its position as purchaser to decide. We take seriously concerns raised about the quality of criminal advocacy, although there is little objective evidence on this issue. Nevertheless, these concerns are a key driver behind the introduction of QASA by the Bar Standards Board, CILEx Regulation and ourselves (collectively known as the Joint Advocacy Group or JAG). We note that the CPS scheme was always intended to converge with QASA.

QASA has now been upheld by the Supreme Court as a lawful and proportionate response to concerns about the quality of criminal advocacy. It provides a mechanism to assess the standard of criminal advocates so that advocates can be prevented from practising beyond their level of competence. It will offer a high level of protection for the public, and it is important that there is no further delay to its introduction.

We do not see what benefits an additional panel scheme would be able to offer over and above those offered by QASA. We would also caution that the introduction of another scheme to assess the quality of criminal advocates runs the risk of conflict between the two systems, damaging the credibility and effectiveness of both.

As well as assessing individual advocates, QASA will provide evidence about the general quality of criminal advocacy. It will help us to identify:

- whether, and if so to what extent, criminal solicitor advocates are acting above their level of competence;

- whether there are common or thematic issues with the performance of solicitor criminal advocates which might need further targeted training and assessment;

- the scale and extent of poor quality advocacy and whether it is localised to particular types of entities or individuals;

- any difference in performance between solicitor advocates and barristers.

This information will enable us and the other members of the JAG to develop an appropriate regulatory response to any issues identified.

QASA will allow us to take an evidence based, targeted and proportionate approach to addressing performance concerns both at an individual and sector wide level. These measures might include:

- restricting an individual from undertaking advocacy altogether, or at a particular level;

- requiring individuals to undertake appropriate training and development;

- reviewing how we authorise solicitor advocates in general or our requirements for their continuing competence.

We would be concerned that taking untargeted regulatory action, without objective evidence of where any quality issues lie, could result in additional costs and barriers to competition. It could have a negative impact on access to justice and could bring the quality of advocacy down.

The challenge for both the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and the Legal Aid Agency (LAA) in this area is the same as for any purchaser: how to get the right volume of work at the right price and the right quality. The pool of possible advocates has already been narrowed substantially by only allowing:

- authorised persons

- that have been granted rights of audience, and

- have been shown to be competent criminal advocates through QASA

to operate in this market. The regulators of criminal advocacy will ensure competence. As in any other market and with any other purchaser, the MoJ and LAA can choose to buy higher quality if they wish but this will typically come at a higher price. However, if the MoJ and LAA are satisfied with the high standards set by the regulators and tested by QASA they have three options: panels of the type outlined in this consultation, competitive tendering and price competition. We consider that price competition would be the simplest option, and this is what the UK economy is built upon.

Moreover, the analogy to be drawn between the CPS and LAA is not an exact one. The market for criminal defence advocacy is not the same as that for criminal prosecution advocacy; while substantial amounts of defence advocacy are privately funded, there is a negligible amount of privately funded prosecution advocacy. There is therefore far greater scope for the introduction of a panel to have unintended consequences for defence advocacy.

We would also caution that delivering conditions favourable to the self employed criminal bar may lead to other bars wanting similar conditions in the future. Proposals should not favour one professional group over others. This would undermine the market improvements secured over the last ten years and rule out potential opportunities to deliver a liberal and competitive legal market that works for consumers.

Q2: If a panel scheme is to be established, do you have any views as to its geographical and administrative structure?

We do not have any views on this point.

Q3: If we proceed with a panel, do you agree that there should be four levels of competence for advocates, as with the CPS scheme?

We consider that, if any panel scheme were to go ahead, it should align with the levels of competence used in QASA. This will increase:

- clarity for criminal advocates on the type of advocacy work they can undertake under both the panel and QASA scheme

- understanding and confidence for consumers of advocacy services (including the judiciary) that an advocate is competent to deal with their case.

Q4: If we proceed with a panel, do you think that places should be unlimited, limited at certain levels only, or limited at all levels? Please explain the rationale behind your preference.

We would urge caution before any limit was placed on numbers, which could lead to unintended consequences. The key issue is that standards are met. Limiting the number of suppliers in any market will inevitably push up prices. It will also reduce your chance of using market pressures among your suppliers to drive up levels of quality. Before proceeding with any limit on place numbers it should be clear what policy objective any such restriction is designed to achieve, the benefit that is expected from imposing that limit, and whether that will outweigh the potential disadvantages.

Q5: Do you agree that the government should introduce a statutory ban on "referral fees" in publicly funded criminal defence advocacy cases?

We already prohibit referral fees in publicly funded criminal defence advocacy cases. Chapter 9 of our Code of Conduct states that the following outcome must be achieved:

you do not make payments to an introducer in respect of clients who are the subject of criminal proceedings or who have the benefit of public funding;

This rule was inherited from the Law Society in its previous role as a joint regulatory and representative body. The ban on referral fees in civil cases was lifted in 2004 after pressure from Office of Fair Trading (OFT) and the likely Government response to the OFT's Competition in the Professions report. However, perhaps because of the lack of competitive pressures in criminal market and to align with contracts for criminal legal aid, which banned these types of fees, the Law Society retained its ban in criminal cases.

It is important to note that there is little or no hard evidence of the use of referral fees in criminal legal aid cases. Allegations that they exist have been frequently made yet, even though information has been requested by the SRA in order that we might tackle any such cases, it has not been forthcoming.

In a recent consultation on improving regulation we asked for evidence on how the current ban works in practice. We received around 100 responses to this question. Some responses stated that referral fees were reprehensible, particularly where public funds are involved. Others highlighted arrangements that could incentivise referrals without breaching the ban, and suggested that however any prohibition was worded some practitioners would always comply with it creatively.

There are a variety of operational and structural devices that make referrals unnecessary. None of these remove the requirement on a solicitor to ensure that an advocate is competent for the work in question. Vertical integration is an important route for the legal market to improve efficiency and customer service at lower prices. Without this option it is likely that double handling between law firms and self employed advocates will drive up costs. In legal aid it is likely that the cuts in fees in recent years have at least in part been absorbed by an increasing level of vertical integration. This is evidenced by the number of barristers working within law firms and the increasing use of in- house advocates (who may be solicitors or barristers). Discussions with criminal law firms confirms this. Vertical integration simply mirrors the fused profession that exists in many jurisdictions without losing the advantages that come from the separate branches of the legal profession in our jurisdiction.

Q6: Do you have any views as to how increased reporting of breaches could be encouraged? How can we ensure that a statutory ban is effective?

We do not have any views on this point.

Q7: Do you have any views about how disguised referral fees could be identified and prevented? Do you have any suggestions as to how dividing lines can be drawn between permitted and illicit financial arrangements?

As above.

Q8: Do you agree that stronger action is needed to protect client choice? Do you agree that strengthening and clarifying the expected outcome of the client choice provisions in LAA's contracts is the best way of doing this?

Consumers needing an advocate are protected by their solicitor being bound by our principles. In particular, principles one to six should guide solicitors' behaviour in this area*. Solicitors must always act in their client’s best interest in advising who should conduct the advocacy in their case.

Careful consideration would need to be paid to the impact on the administration of justice and client experience before any changes were made to the LAA's provisions. This would be especially the case in relation to clients that are vulnerable or in distress. We would not agree that strengthening the provisions is the best course of action without further evidence being collected on potential impacts. We would also question how this would be enforced, and suggest that relying on the courts to police this requirement would be an inefficient use of court time.

We are aware of concerns that have been raised by barristers about firms of solicitors abusing their control of the flow of criminal work by retaining advocacy in-house when the firm has an insufficient number of competent advocates to undertake it. We have no concrete evidence of this practice. Nevertheless, we issued guidance in March 2014 to remind solicitors of their responsibilities when instructing a barrister. We have also committed to the judiciary that as part of the QASA two review year research project, we will undertake some targeted regulatory activity to look at firms' practice patterns to ensure they are meeting the required standards and not contributing to poor advocacy in any way. We note the findings of the Thomson Review of rights of audience in the Supreme courts in Scotland, which asked:

the question of whether a solicitor should be able to instruct a solicitor advocate in their own firm. The benefits to clients include, for example, a solicitor who has represented a client in the sheriff court can continue to do so in the High Court of Justiciary, or commercial clients being able to benefit from a "one stop shop" for commercial litigation. These benefits seem to us to outweigh any drawbacks and we see no issue with this practice. However, this has to be in the context of full observance of Rule 3 [acting in the best interests of the client] by the solicitor.

It is key to take into account the evolving market for criminal advocacy. Even in this relatively traditional area, innovations continue as a result of the removal of artificial barriers to competition. For example, about 20% of barristers practising in England and Wales (about 3,120 individuals) are employed barristers in the public or private sectors. A significant number of these are employed by and practise within solicitors' firms. The BSB says that there are 2,300 barristers working in SRA regulated entities - that is 15% of all barristers. CPS advocates are a mixture of those without higher rights (solicitors and legal executives) as well as barristers and solicitor advocates with the right to practise in the higher courts.

Since April 2015, barristers have been able to form entities and be authorised and regulated by the BSB. Restrictions on the conduct of litigation have also been lifted (since the new BSB Handbook was launched in January 2014). These changes are significant. Like solicitors, barristers are now able to organise in many different ways and provide the full range of services to clients. Barristers practising through an authorised entity are able to bid for legal aid contracts, in competition with solicitors' firms. While it is perhaps too early to determine the extent to which barristers will take advantage of new practice models in order to bid for legal aid contracts, the removal of structural limitations on barristers goes a long way to address the claims of unfairness made by the Bar in respect of solicitors controlling the flow of more profitable legal aid cases.

These developments are to be expected for this market. Legal executives, conveyancers and trade mark and patent attorneys have always worked predominantly in solicitors’ firms and now 15% of barristers do. This benefits consumers by:

- improving choice through the added option of integrated advocacy and litigation

- improving quality by making expert advisors and advocates directly available

- reducing cost by removing duplication (for example, costs related to case handling, of premises, or back office functions).

Increasing competition also reduces the power and ability of suppliers to withdraw their services from the market in a coordinated manner, leading to increased costs, consumer detriment and damage to the rule of law and the proper administration of justice.

The increasing pattern of advocacy being undertaken in-house is not of itself any indicator of quality, or of solicitors undertaking advocacy when they are not competent to do so. Nor is it appropriate for this to be the subject of inter-professional rivalry. Rather it is the market responding with new business models to offer services more efficiently, leading to greater variety in where and how advocates practise.

We would reiterate that we completely support the need for highly experienced and skilled advocates to deal with the most complex cases such as murder, financial crime and sexual offences. However, we expect that the MoJ will hold statistics showing how small a number of QCs there are, compared to the total number of criminal advocates. These skilled advocates will probably always be self-employed and spread across cases at different firms, but that does not mean they have to be self-employed while undertaking their initial training or through the early years of practice where they hone their skills and gain experience. Firms can offer high quality training with experience of litigation, client handling and lower level advocacy in a safer and supported environment. This is the norm in other jurisdictions without a split profession. It is worth noting that on average solicitors have ten years experience before they become Higher Court Advocates – ten years in which they learn and develop undertaking important (but lower level) advocacy and other work within the structures that a law firm can offer. We are not calling for fusion of the different branches of the profession. We are calling for client choice in a competitive market driven to deliver quality.

* Principles 1 - 6 state that solicitors must:

1. uphold the rule of law and the proper administration of justice;

2. act with integrity;

3. not allow your independence to be compromised;

4. act in the best interests of each client;

5. provide a proper standard of service to your clients;

6. behave in a way that maintains the trust the public places in you and in the provision of legal services

Q9: Do you agree that litigators should have to sign a declaration which makes clear that the client has been fully informed about the choice of advocate available to them? Do you consider that this will be effective?

We see no reason to introduce a requirement on litigators to sign a declaration. Solicitors are already bound by a regulatory requirement to act in their clients' best interests and deliver a proper of standard of service. A more specific rule would duplicate this requirement and create regulatory bureaucracy.

JAG consulted on the introduction of client notification in July 2012. Responses (from both solicitors and barristers) suggested implementation would be unworkable both because information about the choice of advocate available could confuse vulnerable clients, and because monitoring and enforcement would be difficult. JAG did not proceed with implementation of client notification.

We remain of the view that it is not appropriate to impose further requirements about advising clients on choice of advocates. There might be occasions when to do so would be inappropriate, and we consider that the decision about how to advise a client should be left to the professional judgement of a solicitor. As part of the implementation of QASA, we have agreed to issue information to all those solicitors engaged in criminal advocacy to remind them of their regulatory requirements to act in their clients best interests and deliver a proper standard of service.

We reiterate that specific rules in this area would be hard to enforce and easy to get round. Relying on the courts to police this type of requirement would be inefficient and ineffective.

Q10: Do you agree that the Plea and Trial Preparation Hearing form would be the correct vehicle to manifest the obligation for transparency of client choice? Do you consider that this method of demonstrating transparency is too onerous on litigators? Do you have any other comments on using the PTPH form in this way?

For the reasons stated above, we do not think this is an effective or efficient use of the court's resources.

Q11: Do you have any views on whether the government should take action to safeguard against conflicts of interest, particularly concerning the instruction of in-house advocates?

We are not aware of any evidence of detriment to consumers that would warrant this type of action. Without further investigation any action would appear to be anti-competitive and to add costs. We would also question why this would be necessary in criminal work if it is not in civil matters.

Q12: Do you agree that we have correctly identified the range of impacts of the proposals as currently drafted in this consultation paper? Are there any other diversity impacts we should consider?

When developing QASA we modelled the cost impact on solicitors being accredited under the scheme. We found that at certain levels if the cost of accreditation was too high it could have a disproportionate impact on certain groups of solicitors. Our modelling suggested that this could lead to specific consumer groups not being able to access solicitors. The impact on solicitors and their employers of any charge for panel membership, given the cost of accreditation under QASA, should be also monitored.

Q13: Have we correctly identified the extent of the impacts of the proposals as currently drafted?

As above. We are unaware of any evidence of detriment in relation to the quality of criminal advocacy which cannot be addressed through QASA. We are also unaware of evidence of detriment in relation to advice to clients on choice of advocacy services. We are concerned that the justifications for the proposed market restrictions are not made out and that they could be challenged on this basis.

Q14: Are there any forms of mitigation in relation to the impacts that we have not considered?

From 1 November 2016 we will introduce a new approach to ensuring that solicitors remain up to date and competent to practise in their chosen field. The new approach will apply to solicitor advocates in relation to the standard of their advocacy. It requires them to regularly reflect on the quality of their work and address learning needs to ensure they provide a proper standard of service. Solicitors must make an annual declaration to us that they have done this.

We will monitor the information this provides as part of our risk assessment in relation to individual solicitors, and market segments.

Q15: Do you have any other evidence or information concerning equalities that we should consider when formulating the more detailed policy proposals?

We do not.

Annex - The shape of the market for criminal advocacy

Changes in demand

All available evidence suggests that the amount of criminal advocacy work is reducing and changing in nature, with the majority of criminal defence advocacy being carried out by solicitors in the lower courts. Combined with changes to legal aid funding, these factors are inevitably having an impact on the criminal law market.

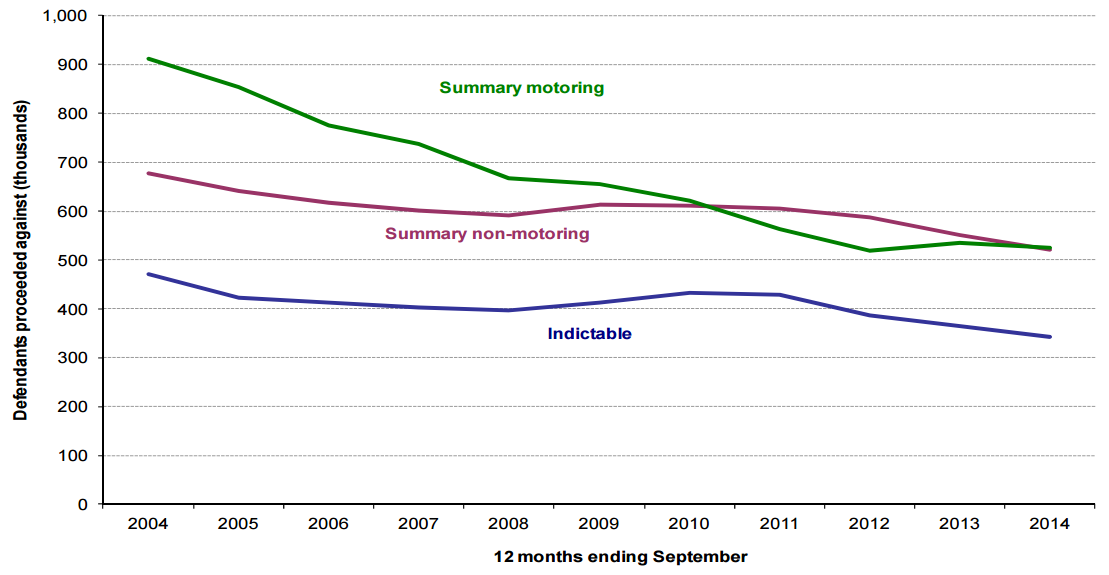

Almost all criminal court proceedings start in a magistrates' court, with lesser offences being handled almost entirely at this level. The graph of Ministry of Justice statistics below illustrates the overall decline in court proceedings at the magistrates' court. The number of defendants prosecuted for an indictable offence fluctuated between 2004 and 2010, after which time they have fallen.

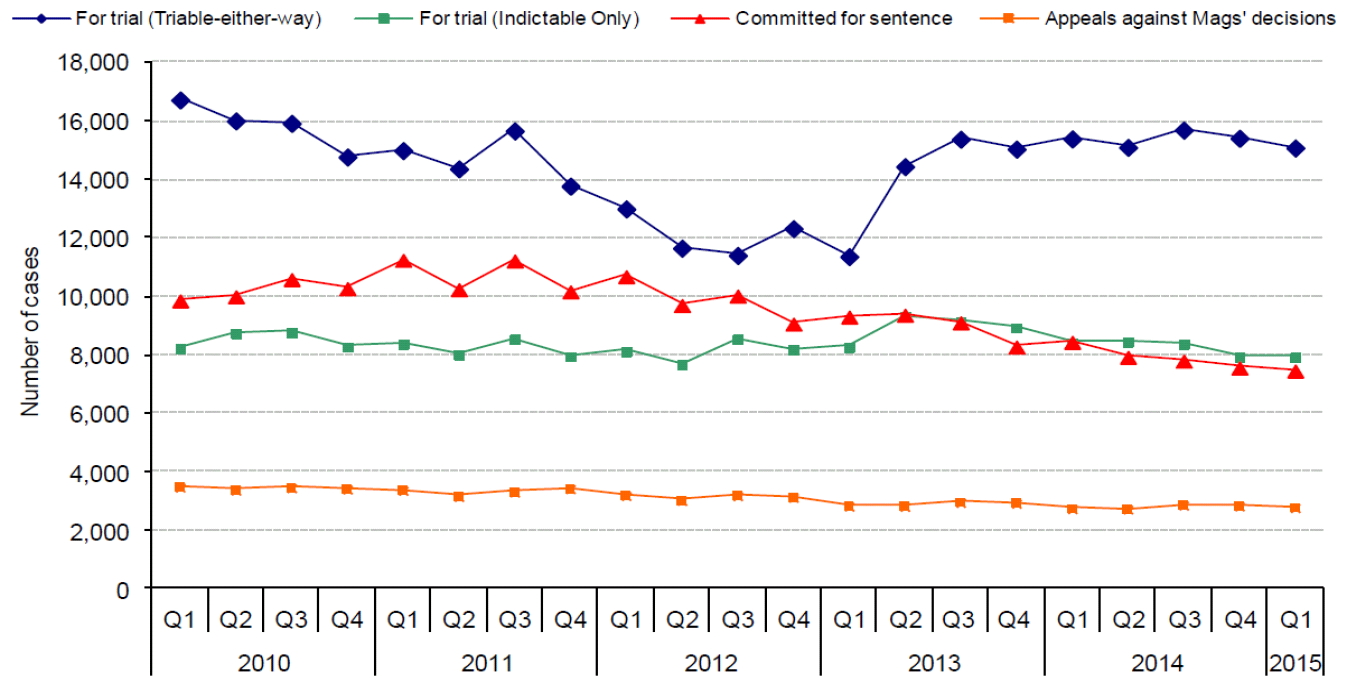

In 2014, 80% of defendants proceeded against at a magistrates' court were dealt with within the magistrates' court, with 7% sent for trial at the Crown court. Following a peak in the number of cases received by the Crown court in the third quarter of 2013, there has been a downward trend in the number of receipts to quarter 1, 2015. There were 33,357 cases received by the Crown court in the first quarter of 2015, a decrease of 5% from the same quarter in 2014.

It can be seen that while trends in Crown court receipts have been downwards, the reductions in the more serious and complex cases (indictable only and committed for sentence and appeals against Magistrates' decisions) have been relatively small across the period. Legal Aid Agency statistics outline the number of legally aided high cost crime cases in the Crown court over a similar period. These show just how very few complex cases there are in the criminal courts.

| Financial year | High cost crime cases opened | High cost crime contracts opened | High cost crime contracts closed | High cost crime expenditure (£'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 33 | 264 | 460 | 93,087 |

| 2011-12 | 28 | 227 | 292 | 91,739 |

| 2012-13 | 20 | 112 | 221 | 67,665 |

| 2013-14 | 12 | 75 | 219 | 56,776 |

| 2014-15 | 3 | 31 | 110 | 36,179 |

Changes in supply

The criminal justice system needs a variety of practitioners to deal with the whole range of cases, from lengthy and complex to straightforward and routine. Effective competition between a range of regulated legal professions is most likely to produce the variety required and enable the profession as a whole to respond to changes in demand. Changes in legal aid funding, including the relative attractiveness of litigation and advocacy, have driven law firms to make business decisions about their practice including undertaking more advocacy. This has resulted in them employing barristers directly and most recently barristers undertaking litigation and looking to deliver wider criminal law services. The preservation of old patterns of practice within individual branches of the profession is likely to do the opposite, ultimately driving up the cost of services and leaving the profession ill equipped to respond to the changes demanded by consumers. Regulation that protects old forms of practice is likely to do so at a higher cost for the purchaser. In a properly regulated professional market, competition can help improve quality.

Most cases are dealt with in the magistrates' courts. In addition, a large number of cases in both magistrates' courts and the Crown court do not proceed to full trial. Of the total number of completed criminal cases heard in both Magistrates' courts and the Crown court, only 1.8% were disposed of by a full Crown court trial following a not guilty plea.

The table below shows the number of solicitors and solicitor advocates, categorised by QASA level and the courts where they work. Solicitors at QASA level 1 do not have higher rights and may appear only in the magistrates' courts. Solicitors at QASA levels 2 - 4 have a Higher Rights qualification and have rights of audience in all courts. The table shows that about three-quarters of solicitors doing criminal advocacy do not have a higher rights qualification and work exclusively in the magistrates' courts. Barristers undertake about 68% of cases in the Crown Court, compared with 32% of solicitor advocates. The BSB estimates that about 5,500 barristers currently undertake criminal advocacy.

| QASA Level | Number | % of all solicitors undertaking criminal advocacy |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - Magistrates court, least complex work | 7,341 | 68 |

| 2 - Higher court | 1,739 | 16 |

| 3 - Higher court | 1,151 | 11 |

| 4 - Higher court, most complex work | 508 | 5 |

| TOTAL | 10,739 | 100 |